Part 1: "What Monkey?"

Part 2: "The First Hike"

Part 3: "Flesh and Blood"

Part 4: "Paranormal Bigfoot"

Part 5: "Tree Structures"

|

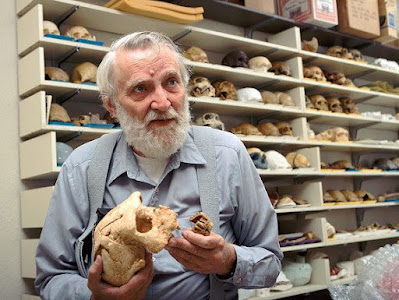

| Saw a sticker like this on a car in Pueblo last week |

All morning on the way to Monkey Creek, I had seen the humor in the situation.

I am not a "Bigfoot guy" in any real way. It's more like I am up in the cheap seats, listening to some podcasts (notably Timothy Renner's Strange Familiars), looking at a few websites, and that is about all. I don't have a "Gone Squatchin'" bumper sticker or even a Colorado-flag Bigfoot decal on the rear window as a symbol of wildness.

Yes, the "Monkey Creek" name was intriguing, and I plan to try again to find a source for it. But this was just a day trip, with some post-hike fishing planned on the South Platte River.

Then I looked up into the old burn.

|

| Note that branches are laid on both sides of the fallen tree trunk in the foreground, whereas the stacks further away are more conical. None have room for anyone insde them. |

My eye was caught by multiple stacks of wood. At first I thought, "Slash piles." But that could not be right.

When forests are thinned for fire mitigation, large logs are hauled away while saplings, tree tips, and branches (collectively, "slash") are stacked, allowed to dry, and then burned when there is snow on the ground. This is a labor-intensive process, and where conditions permit, contractors will sometimes use large machines (masticators) that just chew smaller trees into wood chips and spray those out.

But this was not mitigation, this was a wildland fire from decades ago. Firefighters building a line may toss chunks of burning wood into "bone piles," so that they will burn up and not be a problem, but they do not leave slash piles for later.

And who would build a slash pile over a fallen trunk that would smoulder on indefinitely?

|

| Close-up of the foreground "pup tent" stack. There is no room inside—it's all sticks. |

The piles were clearly built some time after the burned trunks had fallen, using a mixture of charred and unburnt wood. They could not be shelters — there was no room inside, not even for a little kid. Therefore, I ruled out any kind of survival training, like Boy Scouts or US Air Force Academy cadets learning "escape and evasion" tactics. (They do that, but usually in the Rampart Range closer to the Academy, I think.)

So not slash piles for later burning and not shelters either. What does that leave?

|

| Two of several conical stacks of wood. |

|

| Note that the pile in the shade is laid against a log — not how you build a slash pile for burning. |

Unlike some of the claimed "tree structures" that might be the result of wind + gravity, these structures were definitely created deliberately. They would not work as shelters, and they do not seem to be connected to forestry practice as I know it — and I grew up with that stuff. I do not read them as created for wildlife habitat either, not at 10,500 feet (3200 m.) in an Englemann spruce-dominated forest.

An ambitious person could have built them all in a morning's work, but why? For future pyromania? Just to mess with people coming up a lightly used trail who have Bigfoot on the brain?

I saw two "pup tent" structures laid against logs and at least six "tipi" structures scattered up the ridge. So that was a fair amount of work if it was just for fun.

Or what? I have admit that I started feeling a little strange, like that was enough for one day and now it was time to drive out, stop in Fairplay for a burrito, and then go fishing. If the structures were kind of a prank, well, it worked. If not a prank, then it is a mystery to me.