|

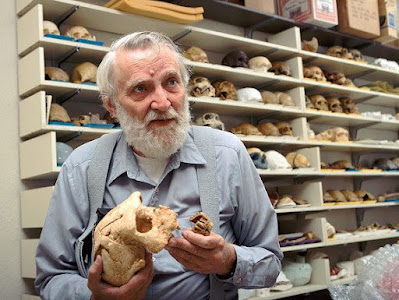

| Anthropologist Grover Krantz poses with his skulls. Image credit: Alchetron, CC BY-SA |

Grover Krantz (1931–2002) was a respected physical anthropologist teaching at Washington State University — but not always respected. His longtime advocacy for the existence of a giant primate (Bigfoot, Sasquatch) in the Pacific Northwest cost him professionally. with other anthropologists calling his interest in Sasquatch "fringe science."

"He couldn't publish his articles on Bigfoot in peer-reviewed journals, and he didn't seek the research grants," [Professor Bill] Lipe said. Because of all the time he devoted to Bigfoot, he said, Krantz wasn't as able to do what he needed to secure promotions and tenure.

"The evidence never got any better," Lipe said. "Grover, to his credit, always approached this as a scientist. He wanted to make sure this theory, however unpopular, got a hearing. In taking on this role, I think he lost his skepticism. . . .

"Within the established academic community, Grover was the first one to stick his neck out," said Loren Coleman, a cryptozoologist (one who studies creatures not yet officially identified) at the University of Southern Maine in Portland.

Krantz had two degrees from UC-Berkeley, and its alumni magazine published a lengthy profile in 2018: "The Man, the Myth, and the Legend of Grover Krantz."

Though Krantz never found a Bigfoot dead or alive, he had what he thought were close calls. Once, returning from an expedition with students in central Washington, Krantz was driving through a snowstorm when something large and brown loped quickly across the road, causing Krantz to slam on the brakes, said Krantz’s former student, archeologist and physical anthropologist Gary Breschini.

In 1992, Krantz published a book, Big Footprints: A Scientific Inquiry into the Reality of Sasquatch with a Colorado publisher, Johnson Books of Boulder, which offers mainly Western regional history, natural history, archaeology, and outdoor recreation (now an imprint of Denver-based Bower House).

In other words, this was an extended middle finger to academia, making his case (based on footprint analysis and other physical data) for the existence of a flesh-and-blood primate that occupied a niche something like black bears in the cool rain forests of the Northwest.

"We have no indication that sasquatch is an endangered species. Its population probably numbers in the thousands and maybe tens of thousands," he asserted."It is a legitimate subject of scientific investigation."

Often called the "flesh and blood" position, Krantz's take on Bigfoot was the original "mainstream" perspective. It is still followed by "citizen science" groups like the North American Wood Ape Conservancy, which agrees with Krantz's position that "Proper scientific study and possible protection will occur only when a type speciman is obtained." In other words, Sasquatch in a cage or on a mortuary table. (They have a new book out on their research.)

The Olympic Project is another organized and persevering research group. Their website states,

The Olympic Project is an association of dedicated researchers, investigators, biologists and trackers committed to documenting the existence of Sasquatch through science and education. Through comprehensive habitat study, DNA analysis and game camera deployment, our goal is to obtain as much information and empirical evidence as we can, with hopes of being as prepared as possible when and if species verification comes to fruition.

While it is possible to envision Krantz's proposed non-hibernating giant primate in the thick forests of the Olympic Peninsula or other Pacific Northwest locations — or even in the dense woods of the Ouachita Mountains where the NAWAC works, Bigfoot sightings are not limited to those places.

They occur in small-town Ohio cemeteries, in Texas suburbs, all sort of places. Usually woodlands are present, but sometimes only a few acres, not a vast and little-visited area.

The Olympic Project makes an appearance in Laura Krantz's excellent podcast mini-series on Bigfoot research, Wild Thing. Krantz? Yes, Grover was a great-uncle. She is a professional radio journalist and producer, so the technical quality of the podcast is superior to most.A 2018 article on Vox.com notes,Krantz walks the line between the facts (which aren’t always on the side of Bigfoot researchers) and our raw hunger to believe in some big missing link out in the woods (bolstered by a surprisingly large number of surprisingly credible eyewitness accounts, some of which she captures on tape in the series’ most memorable episode). It’s smart, well produced, well written, and intelligently structured.

I was always "on the bubble" about Bigfoot, neither "believer" nor "skeptic." Despite attending college in the Pacific Northwest and spending some time backpacking, mountain-climbing, and camping, I never gave the question much thought, and if I did, it was just to assume that Bigfoot was somewhere else.

It was not until later that I was introduced to the concept of "paranormal Bigfoot," which I will deal with next.

No comments:

Post a Comment